The tech giant’s new hub in New York will be close to a growing shelter zone – but can the city fight homelessness while cultivating the market forces that are pricing people out?

Juan Rivera has lived in Long Island City, in Queens, for a month – but has never been to the part of the neighborhood where Amazon will soon establish its New York City headquarters.

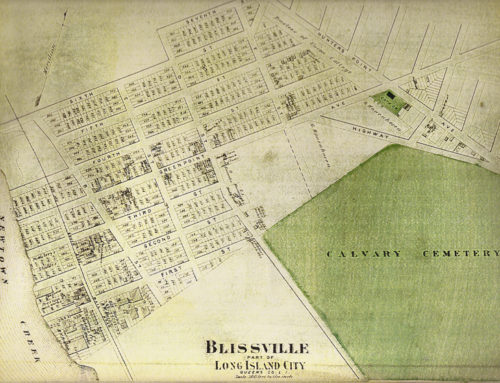

“The only time I leave this side is to go to my program,” says the 28-year-old Puerto Rican native, referring to the methadone clinic he visits in Manhattan five times a week. He spends the rest of his time watching YouTube in his room at his homeless shelter, a former hotel in an enclave of Long Island City known as Blissville.

With his cigarette, Rivera gestures towards the sleek glass towers on the other side of the train yard that divides the neighborhood. “I’ll probably never go over there,” he says. “There’s no reason for me to.”

In all likelihood, Amazon’s incoming workers won’t visit Rivera’s side of the neighborhood, either. They will be more interested in the luxury waterfront condos with jaw-dropping views, the hip restaurant scene, and fast links to midtown Manhattan. When the deal was announced, such was the scramble for hot property there some Amazon workers were even reported to be buying condos by text.

But the the proximity of Blissville and the assumed development zone for Amazon tells a story of the competing pressures and choices that cities must make, with some experts, and residents, warning the Amazon deal will compound problems for the most vulnerable residents.

Seattle, Amazon’s home city, has experienced rising rents and homelessness in recent years.

New York City’s mayor, Bill de Blasio hailed the deal to lure one of the tech giant’s next major hubs to New York city last November, touting its promise to ultimately bring 25,000 Amazon workers to 4m sq ft of office space on the waterfront site.

But De Blasio has also looked at Long Island City as part of his plan to to tackle New York’s homelessness epidemic, with three shelters with the capacity to house more than 400 people opening in Blissville since 2017.

Now, the number of homeless in tiny Blissville rivals the number of permanent residents, estimated at around 475 people.

‘No basic services’

Blissville hasn’t shared in the wealth that has poured into the other end of Long Island City, with its windswept expanse of warehouses and autobody shops abutting Newtown Creek, a Superfund site.

“There’s no basic community services here, no supermarkets, playgrounds, parks, libraries, churches – nothing,” says resident Warren Davis. “The city neglects us because people here are working class, or undocumented.”

Until 2001, Davis lived on Amazon’s side of the neighborhood, back when it was gritty and quiet. “What Blissville is now, that’s what that side of Long Island City was then,” he says. Over the past decade, priced-out Manhattanites discovered Long Island City, making it New York’s fastest growing neighborhood. But few of them moved to its Blissville section, which lacks skyline views and is farther from the subway.

Instead, Blissville became a focus of “Turning the Tide,” the mayoral program to consolidate the city’s 360 shelter facilities into a smaller system. The move has exasperated some residents. “When they started coming here, we had some issues,” says Davis. “Trespassing, littering, public drunkenness, open drug use, occasionally some violence.”

He says things have calmed down since the weather turned cold. Rahhid Asif, owner of Midtown Deli & Grocery, says the shelters have actually been a boon for business. “They come in to get out of the cold, then they hang out and buy things,” he says. “I’m selling a lot of coffee these days.”

Rent increases in ‘condo corridor’

Twelve blocks away, across the tracks, coffee sales are up at Toby’s Estate, too – in this case, mostly of the fair trade espresso and pour-over variety.

“I can’t say we were early adopters of Long Island City,” says co-owner Amber Jacobsen, who opened the cafe in 2017. “But this is a great location for us, being so close to a transport hub.”

Housed in a former artist’s studio in the heart of Long Island City’s condo corridor, Toby’s was bustling on a recent afternoon with smartly dressed customers lined up, credit cards in hand. For her part, Jacobsen believes Amazon will encourage more businesses to open nearby. “The more, the merrier,” she says. “The real estate people have been incredibly thoughtful with the curation of the area, trying to attract the right mix of retail.”

That has taken place amid a construction boom that has seen more new rental apartments built in Long Island City since 2010 than in any other neighborhood in the country. Despite the new housing stock, rents rose by 18% here during the same period, according to a StreetEasy analysis. Now, analysts warn that the arrival of thousands of well-paid tech workers could push prices even higher.

Rents may actually jump even more dramatically in adjacent areas like Blissville. According to a study by the National Bureau of Economic Research, when prices rise, “poor neighborhoods that are in close proximity to the rich neighborhoods are the ones that have housing prices increase the most”.

This creates exactly the kind of conditions that can lead to a rise in homelessness.

In areas of New York where the average rent is under $800, vacancy rates are a paper-thin 1%. This increases the odds that gentrification will lead to displacement, as residents find that once they’re priced out of their homes there are few other places for them to move into.

In addition, Zillow Research found that communities see rapid increases in homelessness when people begin spending more than one-third of their income on rent.

In Seattle, rents were actually in line with the national average until 2010. Since then, they’ve jumped by over 40%. Now the city has the third highest number of homeless residents in the nation.

Amazon chose to build two major new offices, one in New York and one in Arlington, Virginia, after a year-long competition between cities around the US, soliciting bids for a location. In return for the jobs, which Amazon says will pay an average of $150,000 a year, the company will get at least $1.5bn in cash subsidies and tax breaks from New York state, and another $1.3bn in tax breaks from the city. The mayor and governor claim they will come out on top, getting $9 back in revenue for every dollar spent.

But critics like Greg LeRoy of the DC-based Good Jobs First thinktank, which monitors such subsidies, question whether the deal is really good for residents and taxpayers.

Amazon did not respond to a request from the Guardian to comment.

It has previously promised to help fund community infrastructure improvements in Long Island City and provide space on its campus for artists, industrial businesses and a tech startup incubator. “The team did a great job selecting these sites, and we look forward to becoming an even bigger part of these communities,” said Amazon founder and CEO Jeff Bezos in a statement.

Top priority

Mayor De Blasio has made fighting homelessness a top priority.

Under his tenure, rising homelessness rates have leveled off, though they remain at record highs. And while Turning the Tide aims to reduce the number of people in shelters, Amazon’s move to New York, which De Blasio was instrumental in orchestrating, could exacerbate the very problem that the program is designed to combat.

“Most folks become homeless because of eviction, overcrowding, tenuous housing,” says Giselle Routhier, policy director at the Coalition for the Homeless. “Basically, they can’t keep up with the rent.”

That means that in a tight housing market like New York’s, even the gainfully employed can end up homeless.

Ricky Rivers, 30, works nights in a FedEx package sorting facility. Despite the regular paycheck, he says, “I don’t have the money to stay anywhere”. He’s been living at a Blissville shelter until he can find permanent housing he can afford. “It’s just somewhere to sleep during the day.”

Congress member Carolyn Maloney, who represents the district containing Long Island City, says that keeping permanent housing within reach is “one of New York’s biggest challenges”.

“With or without Amazon, New Yorkers are paying increasingly high portions of their income in rent, and not enough is being done to address the needs of people who are very low income, which is exacerbating our homelessness crisis,” she said in a statement.

But for Davis, addressing the needs of permanent residents like those in Blissville is just as important. “What’s happening on that side of Long Island City is starting to make its way here,” he says. “Amazon is going to accelerate that, and people are going to be kicked out of their homes. I don’t want to see that.”

Follow Guardian Cities on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram to join the discussion, and explore our archive here

As 2019 begins…

… we’re asking readers to make a new year contribution in support of The Guardian’s independent journalism. More people are reading our independent, investigative reporting than ever but advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. And unlike many news organisations, we haven’t put up a paywall – we want to keep our reporting as open as we can. So you can see why we need to ask for your help.

The Guardian is editorially independent, meaning we set our own agenda. Our journalism is free from commercial bias and not influences by billionaire owners, politicians or shareholders. No one edits our editor. No one steers our opinion. This is important as it enables us to give a voice to those less heard, challenge the powerful and hold them to account. It’s what makes us different to so many others in the media, at a time when factual, honest reporting is critical.

Please make a new year contribution today to help us deliver the independent journalism the world needs for 2019 and beyond. Support The Guardian from as little as $1 – and it only takes a minute. Thank you.

Leave A Comment